The lights are dimmed, the candles are lit, a little voice begins singing Morning Star, O Cheering Sight and the congregation responds. It’s Christmas Eve, a night full of Moravian traditions. You’re familiar with the service, but do you know the origins of the beeswax candles that you are holding during the Christmas Eve lovefeast?

From the beginning, the small, lighted candles distributed to Moravians in America were made from beeswax. Beeswax, considered the purest of all animal or vegetable waxes, suggested the purity of Christ. The candle, giving its life as it burned, suggested the sacrifice of the sinless Christ for sinful humanity.

Over time greater emphasis came to be placed upon the candle as representing Christ, the Light of the world and the light shed by the burning candle suggesting our Lord’s command, “Let your light shine,” a concept summed up in the children’s hymn:

Jesus bids us shine/With a clear, pure light/Like a little candle/Burning in the night.

Until the end of the nineteenth century, only the children received candles, and this is still the case in some churches. Giving candles to the whole congregation has become an accepted and beautiful part of the Christmas Eve vigils in many places. The grownups are permitted to share in the childlike joy of the Savior’s birth, to become children again, if only for a brief moment. When everyone lived within walking distance of the church, the children tried to keep the candle burning until they reached home, where it would be used to light the candles on the Christmas tree.

The story of the Moravian Christmas candle

In 1747 the world was chaotic with political strife intertwined with religious persecution. The Brethren, who with such vigor had built the church community of Herrnhut were busily building a similar one near the castle of Marienborn in Wetteravia, Germany, as well as being engaged in mission work all around the world.

Marienborn, once a cloister, was now part of a run-down domain whose owner was happy to lease it to the Moravians who, by their industry, were sure to improve conditions. This became a headquarters of the church’s work in the mid-1740s; a school and other buildings were built and many families joined in the work of this new Moravian community.

In the castle the Zinzendorfs and other families met regularly for devotions. As Christmas neared, the children were taught much which would lead them to love their Savior, who was also once a little child.

Thus, on Christmas Eve 1747, Bishop John de Watteville conducted vigil services, using as a theme the happy anticipation of the Christ-child’s arrival. This was not a common idea then.

They sang Christmas hymns, “some antiphonally by the presiding minister and the children, some as solos, some by the whole group.” In this very informal gathering he asked the children questions and they, by their answers, showed their listening parents their clear understanding of the Christmas story. They had even composed some poems which were read to the group.

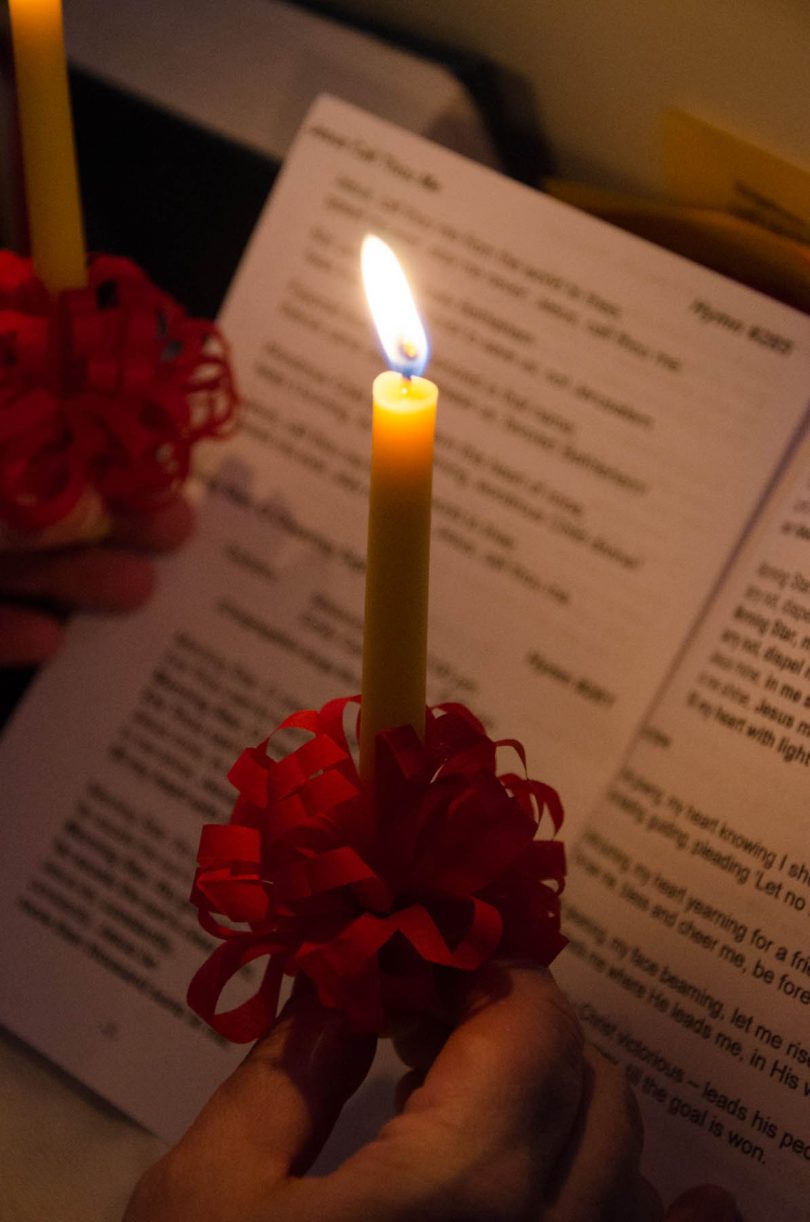

Then Bishop de Watteville spoke of the happiness their knowledge of Christ would mean and “of his kindling a blood-red flame in each believing heart thereby.” Now, making his lesson unforgettable, each child was given a burning candle, with a bit of red ribbon wrapped about the base.

So stirring was this service that the following year one like it was held with the children in Herrnhut. Repetition did not dull it; it quickly became a memory to be cherished, an event to look forward to each Christmas; an established custom.

Naturally the idea was carried to other Moravian centers. The first record in the New World of a candle service like this is in the diary of Bethlehem, Pa., where it was an important event of Christmas, 1756.

These were years of peril. Christmas the year before had been darkened by the massacre of close friends and relatives at nearby Gnadenhuetten on the Mahoning. Then other outlying farms were burned, families captured, killed or scattered. Refugees had crowded into Bethlehem time and again. A constant watch for marauding Indians had to be maintained. The children from Nazareth and other schools had to be brought into the Bethlehem stockade for safety. Many of the youngsters had parents who were away on mission work. For many adults and children it must have been hard to raise their eyes from the immediate dangers and hardships to thoughts of Christmas.

Just two weeks before Christmas a much-loved minister, Bishop Peter Boehler, returned to Bethlehem, having concluded some business in Europe. The devotions he conducted Christmas Eve in the Old Chapel, then the main church building, were long to be remembered as a bright hour in the midst of a dark time.

The town diary has a full account, a free translation of which is:

At eight o’clock the children assembled for their Vigils service in the congregation chapel. After the choir sang the old Christmas hymn, “Today we celebrate the birth,” Brother Peter Boehler talked about the birth of the Savior, using as illustration the Christmas Eve painting which was illuminated and surrounded with the Daily Texts from the past two days. The children took part with Christmas verses, singing them with spirit and tenderness. Then each received a gift as a reminder of the greatest and most wonderful gift when the Savior gave himself to us.

At eight o’clock the children assembled for their Vigils service in the congregation chapel. After the choir sang the old Christmas hymn, “Today we celebrate the birth,” Brother Peter Boehler talked about the birth of the Savior, using as illustration the Christmas Eve painting which was illuminated and surrounded with the Daily Texts from the past two days. The children took part with Christmas verses, singing them with spirit and tenderness. Then each received a gift as a reminder of the greatest and most wonderful gift when the Savior gave himself to us.

And, at last, each was given a wax candle, lighted while hymns were being sung, and before one was aware of it, more than 250 candles were ablaze, producing a charming effect and a very agreeable odor, especially as they sang the concluding hymn.

Brother Peter dismissed them with the wish that their hearts would burn as brightly toward the Child Jesus, as the candles were burning. Then they went happily homeward with the still-burning candles in their hands.

In 1762 lighted candles, symbolizing the flame of love, were used in Bethabara and Bethania, N.C., and in their diary of 1770 it records that they joyfully carried them home, still burning.

The traditional beeswax candle continues to be a central part of Moravian Christmas celebrations. While there are local variations—the size of the candle, how its base is trimmed, how they are presented during Christmas Eve services—the light of the beeswax candle remains a powerful symbol of the light Jesus brought to the world.

Adapted from an article by Lee Shields Butterfield which originally ran in the December 1962 issue of The Moravian.

Early every fall, members at Edgeboro Moravian Church make thousands of beeswax candles.