The epicenter of the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 was Philadelphia, a city of 50,000 inhabitants, which was both temporary capital of the United States and capital of Pennsylvania. The Yellow Fever Epidemic began in August of 1793 and lasted until the beginning of November. During that time, more than 5,000 people died — 10 percent of the city’s population.

The Moravian congregation in Philadelphia was officially organized in 1743. The year 1793 began well for the congregation. In Jul,y the congregation celebrated its 50th anniversary with a lovefeast; several Moravians from Bethlehem arrived to celebrate together with the Philadelphia congregation. On August 13, the Philadelphia Moravians observed the founding of the Moravian Church in Herrnhut. On August 15, a ship from Hamburg arrived with eight single brothers from Europe. They were all housed with Moravians in Philadelphia before they continued on to Bethlehem on August 20. But then, everything changed.

At the end of August, there were rumors about a disease spreading through certain parts of the city. Moravian pastor Meder wrote in the congregational diary: “It is called yellow fever, because those who get it, quickly turn yellow.” Some people left the city. On August 29 Brother Meder wrote about the growing fear: “The fear about the deadly and quickly spreading disease has increased. Many people were busy preparing to flee the city and it looked as if everyone was scared of an approaching enemy and was trying to save themselves by fleeing.”

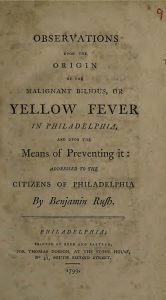

The next day the city authorities asked the population to avoid large social gatherings. It was a Sunday, but the Moravian service had to be canceled anyway because Brother Meder did not feel well. For the next few days, there were no new cases but on September 2, all of a sudden, many people got ill. “Whoever gets sick from this pernicious disease,” Brother Meder wrote, “dies after three, four, or five days at the most. Most have a difficult death and have to endure severe death throes.” It was assumed the disease was infectious and public gatherings were forbidden. What people did not know was that the yellow fever virus does not spread from other people but rather from mosquitoes.

The mayor of Philadelphia asked the churches to report the number of funerals they had performed. Brother Meder, much to his relief, had nothing to report. Even those Moravian families who lived in the affected areas had not seen any cases thus far. Although some other churches still held services, all Moravian worship had been canceled since August 30. Brother Meder was especially sad they were unable to celebrate the Married People’s Festival on September 7, knowing that all the other Moravian churches were celebrating that day. “Our minds were filled with fear and horror.” On September 10 Brother Meder heard about the first death in his congregation:

“Now there were many sick and dying in the area around our Gemeinhaus and church [at the southeast corner of Race Street and Bread Street] and there was great fear in the streets. Many left the city. … In one family three became sick but because of the use of medicine they recovered.”

As there were no real medications, and self-isolating was difficult, many people decided to leave Philadelphia and go to the countryside. It is estimated that during September over 20,000 people left Philadelphia, including many national leaders.

Then Brother Meder and his wife also began feeling ill. Their doctor recommended them to leave the city and stay in the country for a while. The Meders decided to go to Bethlehem.

Brother Meder writes: “We felt sorry for those who stayed behind and we prayed to our merciful Savior for them and for our other fellow men. According to the news we received, the disease spread more and more through the entire city and more and more residents died.

“It was worst at the beginning of October. The communication between the country and the city was restricted from all sides so that those who were outside were unable to go in, and the others could not come out. Many of our brothers and sisters had left the city to stay in different areas. We count more than ninety [Moravians], including children, who were dispersed throughout the country. Those who stayed behind and endured until the end have been unwell all the time.”

Meanwhile, Moravians in Bethlehem were getting nervous. They heard the reports from Philadelphia, and they saw people from Philadelphia coming to Bethlehem or continuing on to Nazareth. These included Moravians, such as the Meders, but also strangers booking rooms at the Sun Inn. Then there were the peddlers, traveling merchants who went from town to town selling their merchandise. People became very concerned the disease could spread to Bethlehem as well. On September 26, 1793, the Overseers formed a committee to consider appropriate measures.

The committee immediately called for travel restrictions on anyone coming from the affected areas. Those from Philadelphia had to quarantine for 12 days before they were allowed to go into Bethlehem. A special eye was kept on the guests of the Sun Inn: no new guests were allowed who had not already quarantined and the existing guests were not allowed to travel back and forth to Philadelphia. The ferryman was not allowed to take any person on the ferry across the Lehigh River that he suspected to be ill. Beggars should not be allowed inside the private homes. These regulations were publically posted in the Sun Inn, at the southside ferry station, in Allentown, and in Easton.

The committee immediately called for travel restrictions on anyone coming from the affected areas. Those from Philadelphia had to quarantine for 12 days before they were allowed to go into Bethlehem. A special eye was kept on the guests of the Sun Inn: no new guests were allowed who had not already quarantined and the existing guests were not allowed to travel back and forth to Philadelphia. The ferryman was not allowed to take any person on the ferry across the Lehigh River that he suspected to be ill. Beggars should not be allowed inside the private homes. These regulations were publically posted in the Sun Inn, at the southside ferry station, in Allentown, and in Easton.

Similar to today, some people were unhappy with the strict rules and tried to evade them. Jacob Ettwein, son of Bishop John Ettwein, wanted to come from Philadelphia into Bethlehem and could not understand why he was not allowed. The committee assured him they had nothing against him personally, but he, like all others, had to quarantine before coming to town. Others wondered what they should do if they became ill while traveling outside of Bethlehem and if this also applied to the boys in the boys’ school. The response was that everyone needed to adhere to the quarantine order and if someone in the family of a school boy was sick, the boy should not come to school for a while.

The committee found it was important to be proactive in case the epidemic hit Bethlehem. The committee prepared two houses where patients could be cared for; simple beds were constructed and linen was purchased for making additional pillows. The expenses were to be shared by all Bethlehem households.

At that time, people were under the mistaken assumption that Africans were inherently immune to the disease, so black nurses often aided the sick. A letter in the Philadelphia newspapers called for black people to offer their services for attending to the sick. The assumption that black people had a natural immunity, of course, was untrue, and many also died. The health committee in Bethlehem heard of this theory and decided to hire black people to nurse patients in Bethlehem in order to be ready as soon as the disease hit. Aside from the fact this medical theory was based on a false racist assumption, it is remarkable the Bethlehem health committee was up to date with the latest medical insights and ready to implement them.

Similar to what health officials are experiencing today, not everyone accepted the committee’s approach. Jacob Ettwein, who was told by the health committee he was not allowed to come into Bethlehem without quarantining for twelve days, announced he would come to Bethlehem anyway. Because of Ettwein’s persistence, the committee invited Ettwein’s brother-in-law, Daniel Kliest, to discuss the matter, in the hope Kliest could talk some sense into Ettwein. The committee acknowledged Ettwein had done much for the sick in Philadelphia but that was exactly the reason he should stay away from Bethlehem. The committee expressed their concern for the particular situation in Bethlehem: people were living closely together in the choir houses, especially in the Sisters’ House and in the Boarding School for Girls. These children were entrusted to the care of the church, so they did not want to take any risks.

Kliest reported back that his brother-in-law only wanted to have lunch with the Kliest family. Since no traveling guest was prevented from having lunch at the Sun Inn, Kliest thought it would be fine for Ettwein to take this same liberty. At this point, the committee capitulated, informing Kliest they hoped Ettwein would only come this one time to Bethlehem, and not repeat having lunch with the Kliests during the remaining period of his quarantine.

On September 28, Moravian doctor Freitag was suddenly called to the Single Brothers’ House to examine what was thought to be a case of yellow fever. After rushing over to examine Georg Neisser, Freitag was unable to confirm that the symptoms were indeed caused by yellow fever; rather “they were the result of excessive drinking.” Although Freitag believed Neisser was not suffering from yellow fever, there was so much anxiety in the Brothers’ House and all over Bethlehem that Dr. Freitag instructed Neisser to leave Bethlehem and stay with his parents for at least ten days.

Fortunately, the epidemic did not spread to Bethlehem. But in Philadelphia, of course, things were very different. Ultimately, fourteen Moravians died: eleven adults and three children. Of course, these deaths were quite tragic but, compared to other denominations, this number was not high. In comparison, the Lutheran pastor had to bury 130 of his members during one week that October.

Overall, 4,044 people died in Philadelphia during the epidemic. The disease even returned several times during the years thereafter and the Moravian diary keeps referring to cases. In 1798, Jacob Ettwein, the man who insisted on breaking the quarantine in Bethlehem five years earlier, died of yellow fever.

Dr. Paul Peucker is archivist for the Northern Province Moravian Church Archives in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. His second installment in this series will appear in our April issue.

Dr. Paul Peucker is archivist for the Northern Province Moravian Church Archives in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. His second installment in this series will appear in our April issue.