On May 5, 2022, Moravians from around the Southern Province came together in an historic brick church in Winston-Salem to celebrate the St. Philips’ congregation’s two centuries of service. The church, which was established in 1822 by Moravians to foster the spiritual life of the enslaved people in Wachovia at the time, remains one of the oldest African American congregations in North Carolina and in the United States.

According to the Southern Province Archives, the seventh oldest church in the Southern Province was born as a mission to fill a great need. In 1822 Salem’s Female Missionary Society noted the absence of religious opportunity for the “Negroes”—the enslaved people—“in this neighborhood,” and petitioned the church leaders to address the matter so that “in the course of time…a church may be built for their own use.”

According to the Southern Province Archives, the seventh oldest church in the Southern Province was born as a mission to fill a great need. In 1822 Salem’s Female Missionary Society noted the absence of religious opportunity for the “Negroes”—the enslaved people—“in this neighborhood,” and petitioned the church leaders to address the matter so that “in the course of time…a church may be built for their own use.”

Br. Abraham Steiner, a veteran of mission service, was called upon to make this mission a reality. Br. Steiner held the first service on March 24, 1822, at the Negro Quarter in the cabin of Bodney and Phoebe with 50 in attendance and two baptisms held. The April 14, 1822, service was also held at the Quarter. The third service was held on May 5, 1822, in the barn on the outlying farm of Conrad Kreuser, and at this service the founding of the congregation was observed-—“a beginning of a small congregation of colored people” with three communicants.

Regular services continued and also included services at Dr. Schumann’s barn and Schober’s paper mill. These places of worship “out of town” served the Black congregation until the consecration of the new church adjacent to the Negro God’s Acre on December 28, 1823. Funded by the Salem Female Missionary Society, the church was built by the enslaved people of logs from timber harvested in the Salem Town Lot and solemnly consecrated to the worship of the Triune God.

Faithful to its calling, the Negro Church was a place of worship, a place of knowing and living into Christ’s redeeming love and forgiveness, a final resting place for departed members, a place of community, a place of refuge, a place of solace, a place to learn to read and write-—taught by sisters of the Salem Female Mission Society, a place to call each other brother and sister.

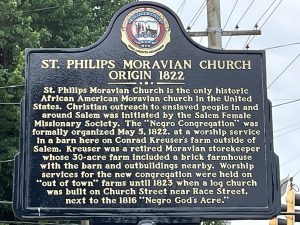

To help commemorate the 200th anniversary of the founding of the St. Philips Moravian congregation, this historic marker was unveiled at the corner of Wachovia and Broad Streets in Winston-Salem. The marker highlights the founding of the church and its significance to Moravian–and American–history. The story of the founders of the church is told on “Salem Walks” offered periodically by the Southern Province Moravian Team for Racial, Cultural and Ethnic Reconciliation (MTR).

St. Philips, Yesterday

With the 1823 log church being for some time too small and inconvenient, the building of the new and larger 1861 sanctuary was undertaken “in reliance upon the help and blessing of the Lord.” On May 21, 1865, a Union Army Chaplin of the 10th Ohio Cavalry read General Orders 32, the formal announcement of freedom, to a packed sanctuary of individuals who were now becoming Freedmen—a grand and proud day for the congregation!

Following the Civil War and during Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era and the Civil Rights movement, the church served as the focal point for the African American community for educational and social functions as well as religious services.

From the beginning of the enslaved worship services in Salem, the church was called the Slave church, the Black church, the Negro church or the Colored church until on December 20, 1914, Bishop Edward Rondthaler bestowed upon the congregation the name of St. Philips Moravian Church.

In Spring 1952, the last regular service was held at the brick church in Salem. The St. Philips congregation moved to the community center in the Happy Hill Garden community. Services were held there until April 5, 1959, when a new chapel located on the Corner of Mock and Vargrave Streets in Happy Hill, was consecrated. The congregation remained in the Mock Street location until the plans for US Highway 52 would send the highway through the church property. Instead of building a new church, the Moravian Church, Southern Province located an existing one, the former Bon Air Christian Church on Bon Air Avenue. On May 4, 1967, the 144th anniversary Sunday of the congregation, the church on Bon Air Avenue was formally dedicated and housed the congregation until it’s 197th anniversary in 2019.

Today and Tomorrow

The St. Philips site in Salem is a sacred and significant place because of its unique relationship to the African American experience. In 1991 it was named to the National Register of Historic Places.

In June 2019, the congregation returned to the brick church in Salem where it currently worships.

Although the congregation’s location has changed multiple times over its 200 years, throughout its history St. Philips has participated in many activities as a force for Christian outreach and social change – helping establish in the late nineteenth century one of the oldest schools for children of color in the state, supporting missionaries in Africa and Nicaragua, supporting Salem Congregation and Southern Province activities and causes, providing training for jobless women, engaging peacefully as individuals in the civil rights movement, providing a vibrant daycare and after school tutoring for children in its community, offering a week-long VBS for all neighborhood children from age three through grade 12, providing breakfast, lunch, school supplies and groceries to each family.

as a force for Christian outreach and social change – helping establish in the late nineteenth century one of the oldest schools for children of color in the state, supporting missionaries in Africa and Nicaragua, supporting Salem Congregation and Southern Province activities and causes, providing training for jobless women, engaging peacefully as individuals in the civil rights movement, providing a vibrant daycare and after school tutoring for children in its community, offering a week-long VBS for all neighborhood children from age three through grade 12, providing breakfast, lunch, school supplies and groceries to each family.

Today, the restoration and improvement of the St. Philips Moravian Second Graveyard, established in 1859 and used until the 1960’s, is a passionate desire for the congregation. Salem Congregation manages this final resting place for over 330 persons, a number of whom were once enslaved. The graveyard is located at the corner of Cemetery Street and Salem Avenue. In November 2021, nearly 100 people gathered to help place new markers on the gravesites of those once enslaved in the St. Philips Moravian Second Graveyard as part of the restoration effort.

Again, faithful to its calling, St. Philips Moravian Church continues to serve others and one another in worship, prayer, visitation and outreach. Strong in its Moravian grounding, its story is the story of the African American experience in our community – a living legacy.

This article was compiled by Peggy Dodson from archival sources and a history of the church by the Rev. Bill McElveen, who has pastored the congregation in recent years. Photos of celebration by Wayne Dodson.