Coffee with Jan Augusta (1500-1572)

Q. Brother Jan, it is obvious that Luke was quite instrumental in strengthening the Unitas Fratrum as an influential force in Bohemia. Following in his footsteps, how did you prioritize your leadership agenda?

A. I admit Brother Luke was a hard act to follow. When I was appointed Bishop I was 32, ambitious and eager to try new things for myself, I established three goals for the Unitas Fratrum:

- to develop legal recognition of the Brethren in Bohemia;

- to unite all Bohemian protestant sects and societies;

- to establish relations with protestants in other countries.

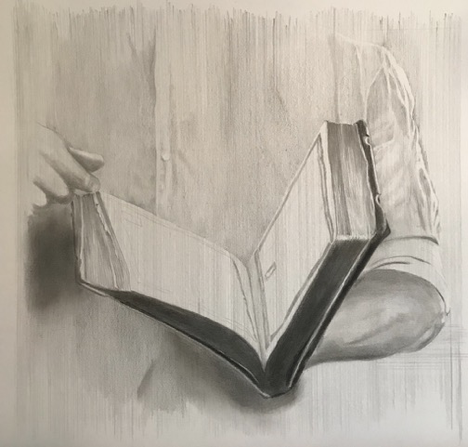

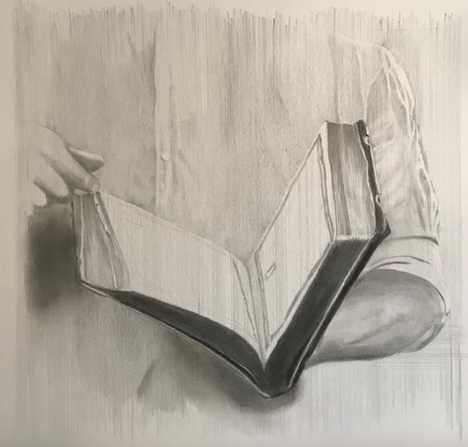

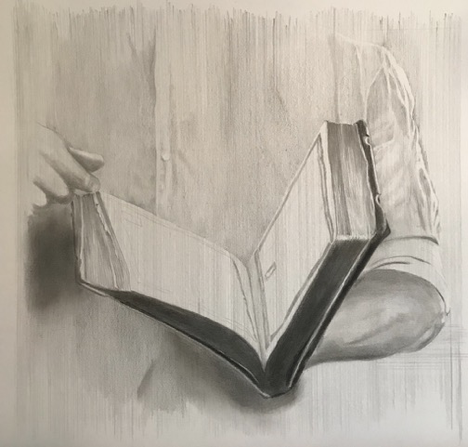

The Kralice Bible was translated by Bohemian Brethren scholars from Hebrew and Greek into the Czech language, then illegally printed by Unitas Fratrum in the late 1500s. This bible remains a national treasure in the Czech Republic. | Drawing by Bill Needs.

Q. How did you go about pursuing these goals?

A. First, I issued an improved “Confession of Faith,” sending it up political channels to reach Bohemia’s King Ferdinand I, and ultimately his brother, the Holy Roman Emperor, King Charles V. It clearly stated that the Brethren had separated from Rome for practical reasons rather than dogmatic arguments. I hoped such wording would dampen any desire for retribution from zealots in the Roman Catholic Church directed toward Unitas Fratrum.

Second, I saw the time was fast approaching when the Brethren would be called to play their part in an emerging European conflict. Contrary to the pacifist stance of our ancestors, I encouraged Brethren to enlist.

Third, I reestablished dialogue with Martin Luther. I believed the Protestant movement in Bohemia and Germany would benefit if a united front was presented rather than divided.

Q. You were ambitious indeed. How did this work out?

A. It turns out differences with Luther could not be resolved. In my mind, the practices of Lutherans seemed to lack the personal discipline and dedication expected of Brethren. I feared a merger might damage our convictions.

For Luther, our views on the Eucharist, our practice of adult baptism, and more were seen as too extreme. My overtures were dismissed when, in 1542, Luther bluntly told me ‘Be you the apostle of the Bohemians, I will be the apostle of the Germans’.

We looked for other foreign sympathies; from Erasmus, Calvin and others. While we received glowing commendations for our practices, there was no desire to unite. In hindsight, it appears nationalistic pride was growing and stood in the way of fulfilling any dream for an alliance of Protestant churches in Europe strong enough to stand against the catholic ambitions of the Roman church.

Q. You describe a climate churning with uncertainty for Protestants. What happened next to the Unitas Fratrum?

A. The political landscape was complicated occasional conflicts and threat of war. In Bohemia, landowners and noblemen continued to protect the Brethren. In Germany, princes backed the growth of Lutheranism. German princes had knights and armament where Bohemian noblemen had only the power of their words and reputation.

Anticipating the Hapsburgs might force Lutherans to recant and return to the Roman Church, the princes in Germany decided to mount a defense against any military attempt. They formed a militia, of sorts, called the Schmalkaldic League. Then they sat back and waited.

For 15 years, King Charles V was preoccupied with Spain and the Ottoman Empire’s invasion of Hungary. The Schmalkaldic League encountered threats. But when the Spanish War ended Charles turned his attention to the Schmalkaldic League and assigned his Brother Ferdinand the task of enlisting Bohemian estates for this fight.

Allow me to spare the painful details. I’ll just say that my recommendations joined Brethren to the wrong side of the conflict. When the Schmalkaldic League was defeated in 1547 King Ferdinand concluded my public directives to the Brethren were contrary to the orders of his brother and Emperor, Charles. He was embarrassed that he was unable to deliver on his brother’s request. He was outraged with me personally.

I was cast into prison in 1548, two years after the death of Martin Luther, and the Lutheran movement was growing in Germany. I suspect authorities feared the same outcome in Bohemia if I was freed. I was tortured and told I would receive freedom only if I publicly recanted my faith. This I could not do. Therefore, I remained in prison for over 16 years. Only after Ferdinand died in 1564 to be replaced by a more lenient King Maximllian II of Bohemia, was I granted my freedom. But terms for my release were that I never preach again. My death, thankfully, came 8 years later.

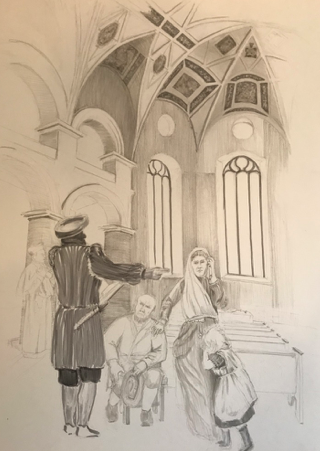

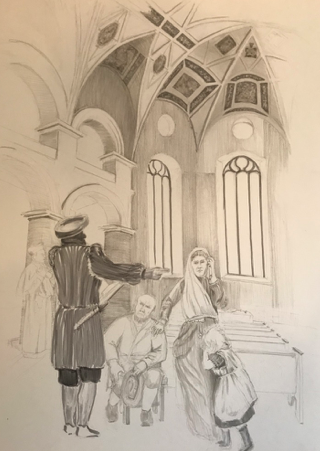

Recant, or be gone!

Ultimatum offered to Brethren in M’lada Boleslav in 1548 | Drawing by Bill Needs

Q. Without your leadership as Bishop, how is it that the existence of the Unitas Fratrum continued?

A. In addition to throwing me into prison, King Ferdinand devised a plot to teach all Brethren a big lesson. He wanted to make an indelible impression while avoiding bloodshed. He issued an order in the spring of 1547 that all Brethren must either return to the Catholic or Utraquist faith or be banished from Bohemia. This must commence within 6 weeks of issuing the edict!

He believed reasonable people would obey and recant their faith in order to continue the lives of peace in Bohemia. While he understood our patriotic dedication to Bohemia, he underestimated the depth of our faith.

Brethren hurriedly called meetings to discuss their options. Each individual reached a decision prayerfully. Within the six week limit, bands of Brethren assembled to pack what they could carry by hand, on horseback or carriage. They bid farewell to their homes, churches, schools, hospitals, businesses, and friends. In the summer of 1547, a tearful journey began from their homeland obeying this unprecedented effort of ethnic cleansing

I’m told two large bands of Brethren moved into Poland. Smaller groups headed to Prussia, Germany, and Holland. Noblemen offered help to the poor or ill. Sympathetic protestants and Catholics alike offered protection and food along the way. It was an incredible sight and likewise an incredible response of neighbor helping neighbor. Nearly 200,000 made that fateful journey from Bohemia into a foreign land, leaving behind 400 empty churches.

Upon arrival to an uncertain destination, refugees experienced varying degrees of welcome or hostility. Some were welcomed to establish permanent residence, based upon the reputation they carried with them. Some were pushed away out of fear of political retribution. Everyone carried precious books of religious instruction, inspiration, and song in order to reinforce their faith while in exile.

Q. What were the consequences of these events, for you and also for the Unitas Fratrum?

A. While I languished in prison, I was told Ferdinand was surprised at how the general population reacted, considering this forced migration unjust. Due to his impulsive actions, respect for the Brethren grew throughout Bohemia and also across borders. The Unitas Fratrum took root and began to grow into Poland.

Meanwhile, a permanent peace was struck in Germany between King Charles and the persistent Schmalkaldic League. Charles realized the Lutheran Church wasn’t going away and continuing battles with protestant (mostly Lutheran) forces was counterproductive. A Peace of Augsburg signed in 1555, essentially stating that whatever religion the local king practiced would be considered the religion of that land. This would apply throughout the Holy Roman Empire, including Bohemia.

It came as no surprise to me that mass expulsion was indeed a mistake and had created a widespread negative impact upon local economies of Bohemia. Lacking skilled workforce and managers, noblemen started complaining. Eventually, noblemen succeeded in pleading their case of hardship. The Peace of Augsburg and the death of Ferdinand in 1564 turned into an invitation for Brethren to begin a gradual return to Bohemia.

For 16 years I remained in prison. I was not forgotten but it became more difficult for me to maintain communication from my cell with what remained of the Unity. Some Elders feared the church might be totally destroyed if no Bishop was visibly active as it’s leader. There existed no authority with whom to negotiate. Nobody told me. Rumors began to circulate that my freedom would never occur or, if it did, freedom would be allowed only upon recanting my faith. This uncertainty prompted church leaders to elect two other Bishops to replace me while I remained in prison.

BY WILLIAM NEEDS |

BY WILLIAM NEEDS |