Pages of history are stained with blood representing horrors inflicted in the name of God. This is no less true than the years between the 16th and 17th Centuries. The Roman Church did not mount an organized response to the Protestant Reformation until the 1534 election of Pope Paul III. Then he began to develop plans to cut the Church’s losses; to retain or replace souls to their membership ledger and to replace cash to their treasury. Rather than delegating the Reformation problem to other kingdoms, he placed the papacy itself at the head of this effort. He initiated what is now called the “Counter-Reformation.”

One humane initiative addressed the obvious lack of education throughout the Church of Rome. To establish educational standards for clerics and parishioners, Pope Paul ordained a society of priests called the Holy Order of Jesus. The “Jesuits” provided education (Christian education and re-indoctrination) for the masses. So began Rome’s response to the educational initiatives started by the Protestants.

Other steps to counter the Protestant advance were not so humane. They required manipulating alliances with existing rulers for the purpose of extinguishing fires for reform by whatever means possible. Bohemia was the obvious hot-bed for Protestantism in Europe, and Germany was quickly gaining traction.

Coffee with Baron Wenzel von Budowa (1560-1621)

Q. Your Lordship, it appears you lived in a time when the Unitas Fratrum regained it’s success, only to again become the object of extreme persecution. Can you explain how that came about?

A. Simply stated, events then were influenced by how the various kings of Bohemia saw their role in the religious affairs of the state. For example, King Ferdinand I supported the persecution of the Brethren as an established practice. Those who were banished from Bohemia were done so by order of the Edict of St. James.

I grew up during the reign of King Maximillian II, who had succeeded Ferdinand. His thinking was much more lenient and progressive. He seemed to regard religion as a matter of personal choice in Bohemia rather than a state dictate, and contrary to thinking of Hapsburgs. The Peace of Augsburg strengthened his position and was seen as a cautious invitation for Brethren to return to their beloved Bohemia.

As I matured into the role of a nobleman, I held a deep respect for the Brethren and their welfare. Our family had been members of the Unitas Fratrum but were titled property owners and chose to remain, joined the Utraquist Church, and continued caring for households on our estate. Nevertheless, the hymnal and texts of the Unitas Fratrum were pulled out of hiding for our private worship. Our family offered food to Brethren as they passed by, and occasional refuge to those needing a hideout.

Q. How did things change with the return of the Brethren to Bohemia in the late 1570s?

A. First, I must describe their return like a joyous welcome of prodigal sons! In fact, that it was. The children of the now aged Brethren who returned as adults, well instructed over years in exile by the words in Luke’s catechism.

Second, the economy began to prosper again. All Bohemia had been suffering financially and socially during the 60-year absence of the Brethren. The children of the ancient Brethren took responsibility to reopen businesses and offer services similar to that of their fathers.

Third, as lord of a Bohemian estate, I felt a renewed energy in social engagement and a sense of well-being. Printing presses resumed work promoting their brand of Christian message wrapped around their pious but practical culture. Schools, orphanages, and social services returned to their good works.

The return of the Brethren was not entirely without problems. Not all pastors returned to Bohemia. During their absence, some had established churches in Poland and remained there. Others drifted elsewhere for refuge or joined the Lutheran Church. Of course, some had died. Where 400 churches once served Moravia and Bohemia now many churches were left as congregations without full-time pastors.

Necessity drove volunteers to duties normally reserved for clergy. Laymen were given titles of “Elders” and “Deacons.” Elders would oversee the spiritual matters or the congregation such as providing support, encouragement, teaching, guidance to members of the church. Deacons would conduct “hands-on” duties such as feeding the less fortunate, maintaining the church building, and caring for the aged, widows, and orphans.

To my knowledge, neither the Roman Church nor the Utraquists Church offered such democratic arrangements. To serve in such a devout enterprise was quite fulfilling. I was proud that my contribution to the Unitas Fratrum had clearly made our Bohemian society the most literate in Europe. I was honored to be chosen to serve as an Elder around the turn of the century. This selection, however, was to bring unexpected consequences.

Q. Unexpected consequences? For an Elder? Would you explain?

A. In contrast to preceding decades, the 14-year reign of Maximillian encouraged a mutual sharing of respect and friendship between all Protestants and Catholics. That peace-filled period was called a “Golden Age.”

Maximillian promised religious tolerance, and we got it even though he never placed this into writing. The “Peace of Augsburg” was altered for his purpose, different from how it was applied throughout the rest of the Holy Roman Empire. When Maximillian died in 1576, his crown passed to his son, Rudolf II, whose management style and personality was stiff and formal, not as approachable as his father. But he did keep the promise of his father to permit religious tolerance. As decades passed, some feared Rudolf’s continuing commitment to his father’s promise might fade away or be called into question. Leaders approached King Rudolf to request a formal proclamation and he answered by preparing a document in 1608 titled the “Letter of Majesty.”

The Letter of Majesty permanently legalized Maximillian’s brand of religious tolerance across all of Bohemian. However, flaws in the document required tweaking, notably how to interpret the term “religious tolerance,” and by whom? A Diet (now known as a committee) was formed to hammer out the details. This committee was to be comprised of representatives from the various churches.

As an Elder for the Unitas Fratrum and a Baron for one of the Bohemian estates, I was a natural choice to represent the ecclesiastical and secular issues before this committee. Accustomed to the Unitas Fratrum practice of sorting out conflicts by applying the logic of essentials versus non-essential, I was extremely uncomfortable in the climate of circular political arguments generated by this committee.

Q. Tell me more about this “Letter of Majesty” and it’s implementation committee.

A. This time, in the early 1600 Bohemia, most citizens claimed loyalty to one of two religious parties of Hussite origin: the Unitas Fratrum and the Utraquists. Only a small number of citizens remained loyal to the Roman Church. They were the minority, along with a few Lutheran immigrants from Germany and some Calvinist immigrants.

What was not well known is this was also a time when a “brothers quarrel” was brewing inside the royal family over who should rule various Bohemian estates. Rudolf saw the Letter of Majesty, if carefully worded, might also solve some of the intra-dynastic rivalries for power and property. This didn’t work out so well.

Unfortunately but perhaps purposely, the Letter of Majesty tried to accommodate too many parties with its vague wording. It was obvious that King Rudolf wanted to continue his father’s wishes, but the committee charged to work out the details represented radically different interests.

Then Rudolf died in 1612, only 3 years after issuing the Letter of Majesty. The throne was turned over to his brother, Mathias I, probably the most inept choice to manage implementing this imperfect edict.

Q. So, were issues with the Letter of Majesty eventually ironed out?

A. Mathias had little interest in the Letter of Majesty so he delegated that responsibility to Cardinal Klesl to represent him on the committee. Klesl had been sent to Prague by Rome to supervise the Catholic Counter-Reformation in Bohemia, so it’s easy to see that he joined us with an obvious bias.

Through Cardinal Klesl, the representation of King Mathias began to change previous promises offered to Protestant groups. This only confounded the Protestants, with each meeting ended with bickering among each other.

King Matthias reigned for only 5 years and left no heirs. Briefly, Bohemian noblemen had an opportunity to influence who would succeed him. But quarreling persisted among the Protestants showing neither a sense of agreement nor maturity to deal with the political games posed by these events. By squabbling, they squandered an opportunity to influence the decision for the next King of Bohemia. Upon his death, Matthias was replaced by Ferdinand II – an ardent Hapsburg and devout Catholic. Ferdinand promptly replaced Cardinal Klesl with his own followers of strict Hapsburg ambition. The composition of the committee now represented Catholics, Utraquist, Lutherans, Jesuits, Brethren, and the Hapsburgs.

The committee continued its work to parse out the details of the Letters of Majesty while I tried to facilitate trust among the parties. An agreement was elusive, those meetings never went well.

Q. Did the“Defenestration of Prague” result from these tensions?

A. Ah, so you know about the Czech tradition of throwing people who disagree out the window? As a matter of fact, tensions played a large part. Fury of the Protestant’s was on full display when the committee met in Prague in the Spring of 1618. King Ferdinand had sent representatives who again retracted promises. They displayed total contempt to rights previously granted to Protestants. I watched tempers flare. Pushing occurred then violence took over. Suddenly three representatives of the King were turned on and tossed out of the window. They fell over 50 feet into a pile of garbage. No one died but egos were badly bruised. Their survival was described by Catholics as a heavenly sign of their God’s Protection. Protestant description was a bit more gross.

This event was not forgotten. Ire increased, further separating the factions. While tense negotiations continued in public amidst an atmosphere of distrust, a war was being planned in private to emerge as a Bohemian Revolt – Protestants against Catholics.

Q. Did war occur only due to the embarrassment of Defenestration?

A. No, plans had been in the making well before the defenestration. The Pope was already rebranding the Church of Rome, adding the name “Catholic” to denote the universal influence of the Church (New World as well as Old). He bribed King Ferdinand to regain the kingdom of Bohemia. Jesuits were cleverly distributed throughout Bohemia to strengthen the Catholic message to the remaining faithful. Plans were made to send advisors to Vienna to evaluate and assist in all efforts to suppress Protestantism.

By our sheer numbers and due to our successes, we Brethren stood out among all the Protestants in Bohemia! Skirmishes occurred for two years following the defenestration testing the readiness of the Protestants for battle. It was obvious to me that the Protestants who were unable to mount a united debate in meetings would be unlikely to mount a military defense in all-out war. The golden age for Protestants in Bohemia, and for the Unitas Fratrum, was rapidly unraveling.

When the Battle of White Mountain occurred in 1620 on the outskirts of Prague, my fears were realized. It was a total rout of Protestant forces: 1,800 were killed, several thousand injured, 700 captured. I feared the time had come when an example would be made of all who dared challenge the authority of Rome and the Hapsburgs.

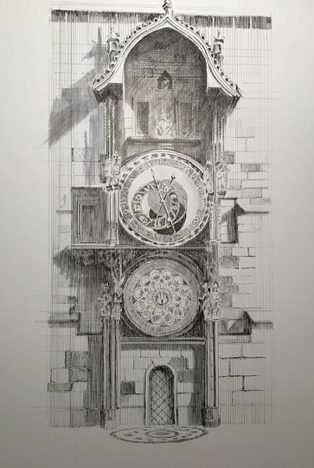

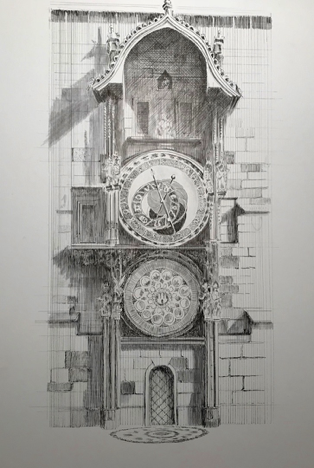

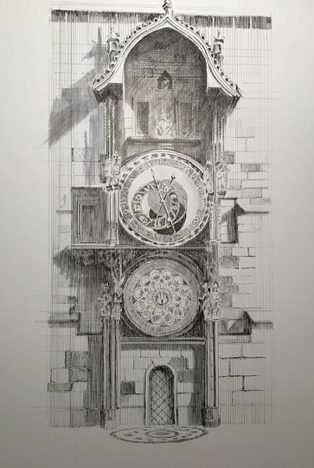

Prague’s Astronomical Clock Tower around the corner from the site of Day of Blood | Drawing by Bill Needs

Q. I’m uncertain if I want to hear what comes next. Would you elaborate on the outcome?

A. To begin with, there was a mass round-up of anyone suspected of participating with attempts to hinder the reputation of the Roman Church or the implementation of Hapsburg rule. The comments I made while serving on the committee made me a suspect. In those days, suspicion was as good as a sentence.

I was one of 27 noblemen led to the gallows on the square of Prague, just around the corner from the Astronomical Clock and in view of Thyn Church. On the morning of June 21, 1621, beheadings began. Executions of criminals are typically held in private.

When executions are held in public they are held with a purpose to impress: a well-choreographed script is followed to assure a deep emotional impact will be leveled upon all who are required to attend and witness the spectacle. There are speeches, flags, drums, and blood.

There were 12 Brethren and 15 other Protestant noblemen. All of us were well known as leaders in our communities, pillars of our churches, advocates for peace. The executioner knew most of us personally so had carefully sharpened both edges of four swords to make his work and our demise efficient and mostly painless. At the hour designated by the chimes of the Astronomical Clock around the corner, the streets began to flow with blood. June 21 is now known as the “Day of Blood” when 27 patriots died in defense of their country and their faith.

Following our execution, our heads were mounted on pikes to be displayed on Charles Bridge where they remained for years as a testimony for any who would challenge the authority of Rome and the Hapsburgs.

Q. But Protestantism did not end? Would you explain what occurred next?

A. The tragic loss of the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, followed by public executions of Protestant nobility, stoked fires of retribution across Eastern Europe. Mind you, for centuries it had typically been religious leaders who were executed for talking against the Church of Rome. This time, it was the laymen, the parishioners, citizens not soldiers who were targets for public execution!

Religious battles broke out first in Bohemia, then neighboring states. These fights were clearly between angry Protestant and Catholic forces, but they quickly expanded when foreign and mercenary troops entered Prague, being paid to play a role in the obvious powershift in Eastern Europe.

1620 marks the date when King Ferdinand II reimposed the rule of the Roman Catholic domination across his land. He was unaware that his action would set into motion a game of war lasting 30 years to change the map of Europe forever. 1618 to 1648 witnessed the most destructive conflict in human history, resulting in eight million casualties, civilian and soldier alike.

Q. And, what about the Unitas Fratrum?

A. King Ferdinand II remembered the words of Pope Alexander VI “to permanently crush the Unitas Fratrum from the face of the earth.” He was relentless in his quest. Brethren were again purged from all the land, this time to never again mount an effective return. Their churches were turned over to the Roman priests. Schools were confiscated by Jesuits. Homes, hospitals, printing presses, and businesses given to Catholic ownership. Noblemen in Bohemia were jailed or slaughtered if they gave any hint of opposition to the dominance of Rome or the rule of the German Hapsburgs.

Bohemian Brethren who did not recant were either sent into exile or murdered. Anyone suspected of offering aid to fleeing Brethren was branded a criminal and subject to the same consequences as the noblemen on the Day of Blood. Life was cheap. There would be no return, especially while war was raging.

Into this chaos entered the last Bishop of the ancient Unitas Fratrum. Jan Amos Comenius, a scholar and a teacher with growing international fame, was chosen by remnants of a church in exile to become Bishop.

Raised in the Moravian Church in Dover Ohio, Bill graduated from Moravian College in 1962. A drop-out of Moravian Theological Seminary, Bill now lives with his wife, Sara in Marietta, Georgia. Bill’s career served disabled individuals and employers in providing realistic vocational choices as a Vocational Rehabilitation Counselor. After retirement in 2004, Bill discovered he had a previously unknown artistic talent for drawing. Now, when Bill and Sara travel, he supplements his photography record with art inspired by the scenes and experiences. For more art, visit Bill’s website at BillNeeds.com. For discussion about art or blog content, email [email protected].

BY WILLIAM NEEDS |

BY WILLIAM NEEDS |