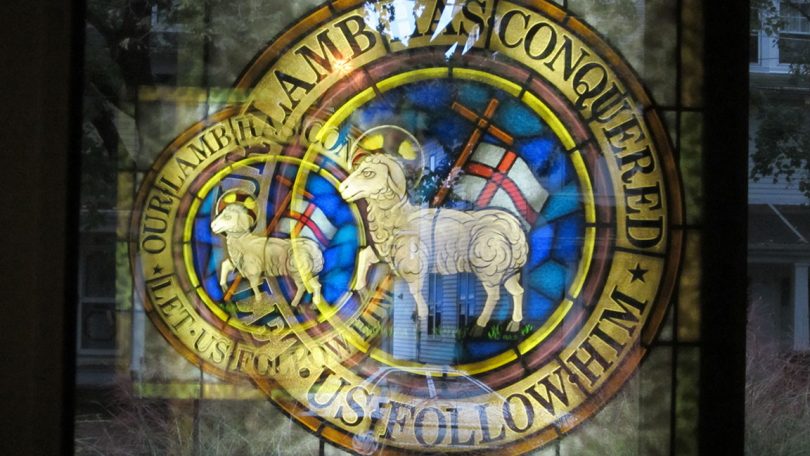

One of the things that I have appreciated about being a follower of Jesus is the inspiration and encouragement I find in how our spiritual ancestors (the Ancient Unitas Fratrum) conceptualized the key aspects of Christian faith and practice. These would eventually be organized as the “essentials, ministerials, and incidentals”. These are highlighted in the most recent edition of the “The Moravian Catechism” (2020) and date to the 1450s.

In the next several additions of the Provincial Ties, I invite you to ponder what our tradition has expressed about the “essentials” and their relevance for Moravian faith and practice today.

It was a blessing to engage in an independent study with The Rev. Dr. David Schattschneider at Moravian Theological Seminary in 1990. It focused on the core beliefs and practices of the earliest group in the Moravian faith family – the Ancient Unitas Fratrum. At the time of the project there were very few resources published in English that captured the story. In recent years new publications have made this accessible (see “The History of the Unity of the Brethren” by Rudolf Rican, translated by C. Daniel Crews; “Faith, Love, Hope – a History of the Unitas Fratrum,” by C. Daniel Crews; and “The Theology of the Czech Brethren from Hus to Comenius,” by Craig D. Atwood.)

What stood out was the expression of organizing faith and practice in three concentric circles. At the core are the essentials. There are critical resources that lead to experiencing and understanding the essentials – which are known as the ministerials. And there are important features of church community life that facilitate these two dynamics – which form the outer circle of the incidentals. These are not separate circles. They remain connected. Everything about the ministerials and incidentals are nested in the core, in the essentials. But what makes up the ministerials and incidentals are not essential in themselves.

What I propose in this series is a brief exploration of the essentials as stated by our spiritual ancestors beginning with “what they are”. And in later additions of the Provincial Ties, exploring “why” – the context out of which these expressions took form. Concluding by “how” the essentials took form in various faith practices and expressions for early Moravian Christian communities.

“The founders of the Ancient Unity had to explain why they rejected some teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church and did not reject others.” (“The Moravian Catechism” – IBOC: 2020, p. 6). By stating the “essentials” it also helped them explain why they could cooperate and collaborate with other Protestant communities while retaining their identity. “They believed that without the ‘essential’ things, a church cannot be a church, and if a church has these ‘essential’ beliefs, it is a church even if it has practices and principles that are different from other churches.” (p. 6) Believing and living out these “essentials” gives witness that we are followers of Jesus.

Technically there is one essential – a relationship with God. We say “essentials” because it has several parts. Most importantly, God’s grace has been revealed in the life, teachings, sufferings, death, and resurrection of Jesus. Our spiritual ancestors described God’s part of this relationship as what has been revealed in scripture and shared experience through God’s actions of creating, redeeming, and sustaining. The human side of the relationship is our call to respond in all circumstances of life with faith, agape-love, and hope. We will explore “ministerials” later, but first and foremost among them is the essential nature of scripture to point to the dynamic nature of this essential relationship-connection to God.

God’s action is the past, present, and ongoing work of creating, redeeming, and sustaining; our part is responding to God’s infinite grace and love with our actions of faith, agape-love, and hope toward God and one another. While we cannot not come to understand this relationship without the Bible, the Ancient Unitas Fratrum did not believe the Bible was part of the essentials. The Bible points to God’s creating, redeeming, and sustaining actions. They held fast to the contention that doctrinal systems or styles of interpretation of the Bible should not be a barrier to our relationship with God. If they help us engage the essential relationship with God, they are useful; but if they become a stumbling block of division and suffering, they should be set aside. Our relationship with God should not be superseded by a particular doctrinal view or interpretation of the Bible.

What I find to be fascinating is how our spiritual ancestors expressed the “essentials” within the context of a living, dynamic relationship with God and one another. This was first and foremost, especially for a community that was newly forming into a Protestant denomination. Full disclosure: the early Ancient Unitas Fratrum grappled with this meaning in each subsequent generation. They saw the ongoing search for sound faith and practice a key part of dynamic connection to God and one another, even though the search can be frustrating and uncomfortable.

This is more striking when you consider the historic context out of which these spiritual understandings of Ancient Unitas Fratrum were formed. Stay tuned for more of the story in the next issue of the Provincial Ties.

Submitted by The Rev. Dr. Neil Routh, President, PEC