A. Our first encounter with Europeans was with explorers, then traders and trappers. We got along well because they also seemed to share our value in keeping balance in the natural world.

But when settlers arrived from European cities, they introduced a new way of thinking. They told us they actually believe that mankind is placed upon the earth to dominate nature, not collaborate with nature. They demonstrate this by their behavior.

Claiming exclusive ownership to land, they clear away trees and animals to establish permanent homes and villages.

We are confused. How can any individual even conceive they could “own” the land, a gift to all from the Creator? If so, can you also own the air, or the water?

We noticed European settlers felt entitled to dominate weaker animals and people, including women and Africans. They used them as tools or beasts of labor to perform their work rather than attempting to understand their differences and to live in harmony with them. Certainly we had slaves captured from wars with other tribes, but they were usually assimilated into our own culture despite their different tribal affiliation, not bought and sold, not beaten or demeaned. In the matriarchal society of Cherokee, women are traditionally given equal responsibility in running the household or running a village. There is no division nor dominance of people. Europeans seem to miss this essential element of living in balance with nature.

Finally, Europeans seem to measure success in accordance by the degree to which men and women gather possessions to increase an appearance of wealth and influence; belongings which far exceed what is needed for oneself or one’s family or tribe. Cherokee measure success by the degree to which they maintain the natural order.

For the Cherokee, this European mind seems bizarre; placing man in a position of authority, even above that of the Creator.

It should come as no surprise that traditional Cherokee leaders thought Chief Vann’s behavior reflected this European way of thinking, and that he had sold-out to the enemy. As his wife, I understand James Vann’s plans made perfect business sense to him. He accumulated wealth, property and slaves with the belief that he could match the richest plantation owners in the South.

Q. I had not considered that insight. But you became a Christian convert, right? How did that conversion happen?

A. My husband was not a perfect man. It was not easy being married to him. He was not easy to do business with. He drank too much and became violent and unpredictable. He was selfish in every way except for his desire to assure dignity of the Cherokee. When he was shot dead in a tavern, he was probably drunk. No friends would speak for him. Indeed his belongings were picked off his body before I found him buried in a shallow grave. He was 18 years older than me. We had no children of our own but he even tried to carry his selfish influence into his death by attempting to use white-man laws to strip me of my Cherokee-ordered inheritance.

He was my husband, however, and I found great difficulty mourning his death. That’s when comfort seemed to come to me from words of Sister Anna Rosinna Gambold, wife of the Moravian missionary. Her unusual sensitivity to my condition was inspired by her God and when I asked to learn more about this sensitivity she began by explaining what she understands about creation.

She said she agreed there is a God-given balance of nature which must be respected. You live in a garden here, she said, evidence that the Creator takes care of us, both Cherokee and European. But, Christian faith understands there are always human beings who want to upset this balance for personal reasons. Don’t you find some Cherokee men and women who don’t agree with your understanding of the Creator and who want to reshape that understanding for their own purpose?

In Christian religion we try to describe this fact of life through stories, beginning with Adam and Eve and what happened after they ate the fruit from one special tree in their garden. The Creator gave them everything they needed, but also gave specific orders to not eat fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil.

This is probably a metaphor, she added, but continued that after “man” and “woman” ate from this tree, they had knowledge that they previously did not have. That knowledge created a desire for more and set their feet on a path away from God the Creator. They became “selfish”; their behavior became “greedy”. Created to be sharing creatures, knowledge of evil as well good caused them to make decisions to live life trying to serve themselves rather than living to serve their Creator. They also became ashamed.

She concluded by explaining this creation story of one man and one woman in a garden represents to Christians all humankind in the world (God’s creation) to illustrate how all of us are inclined to fall away from constantly thanking our Creator for His (or Her) gifts. Instead we try to do things that draw attention to our own personal accomplishments. This behavior we call “sin”.

Sinful thinking and behavior contributes to throwing the natural world out of balance. This makes our Creator unhappy….

Q. You pause. Is there more?

A. Sister Anna Rosinna often paused her comments during our visits. After talking about sin, she paused for me to consider her words. Later she described forgiveness. Then another time she described redemption – and God’s gift in human form, Jesus Christ. I was curiously warmed by our conversations. Sister Anna Rosinna explained that feeling was the presence of the Holy Spirit moving inside me. Each conversation ended with prayer. This inspired me to carry on my own personal conversations with God in a way that was different than the impersonal interaction with the natural world of the Cherokee. In the depression from my husband’s treatment, from the hostility of settlers to my Cherokee people, from the forced abandonment of our sacred lands, I found comfort in the promise of a redeeming God.

I was 27 when I accepted Jesus as my Savior. I also accepted myself as a woman with talents worthy to speak up for the cause of the Cherokee against repeated removal from the lands of our ancestors.

Q. You became a Christian? But you also became an activist?

A. I guess you could say that. My testimony inspired other Cherokee natives to hear what Moravian missionaries were saying and to consider applying these words to their own lives. My testimony did not omit what I considered sinful behavior by Cherokee and Euro-Americans alike who act in self interest, and who abandoned the interests of our Creator and our tribe. My words to tribal and government officials against the proposed Indian Removal Act were recorded and accepted by many even after my death in 1820.

But discovery of gold in the North Georgia hills in 1829 prompted President Jackson to side with settlers who followed their dream for prosperity at the expense of the Cherokee nation. The 1791 Treaty of Holston was rescinded and replaced, over the objections of your Supreme Court, with the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

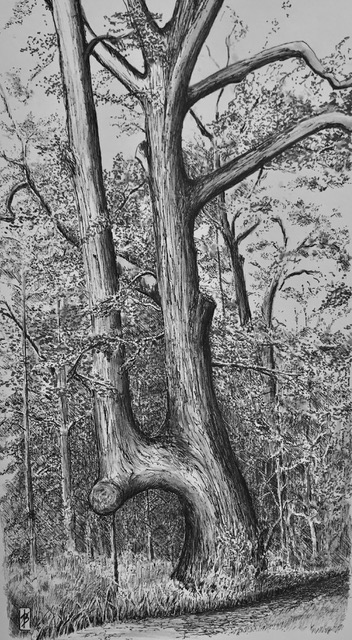

I have nothing more to say about that injustice. To express an opinion only weakens my witness of God’s love for all mankind. Subsequent records will show the US Government forced the displacement of approximately 60,000 people representing “five Civilized Tribes” between 1835 to 1850. It is estimated that 15,000 Native Americans died on the “Trail of Tears”. There were no Trail Trees directing them to refuge.

Sisters in Christ, Anna Rosinna Gambold and Peggy Vann Crutchfield are memorialized today in God’s Acre at Spring Place, GA.